The Politicians vs. The Cartoonists

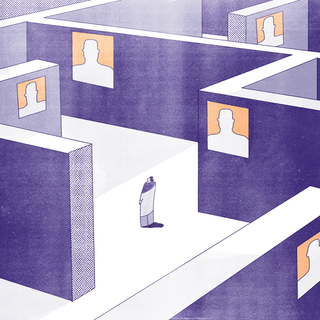

How cartoonists become the face of political satire – and the punishments that follow

After a cartoonist was booked for allegedly depicting Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in an undignified manner, he apologised. Interim protection from arrest was granted only thereafter, and only on the condition that he refrain from sharing further “offensive” posts on social media.

Who are political cartoonists, and why is their work so often criminalised in a democracy?

The history of political cartoons is flush with artists who transform a politician’s appearance into a visual shorthand for Machiavellian cunning. In 1805, James Gillray’s The Plumb-pudding in Danger shows Napoleon Bonaparte and British prime minister William Pitt carving up a world-shaped plum pudding. The cartoon appeared at the height of the Napoleonic Wars.

The world’s warring endeavours have long provided political cartoonists with a steady stream of material. In 1939, New Zealand–born cartoonist David Low depicts Hitler and Stalin genially greeting each other after their joint invasion of Poland in Rendezvous. As Low noted, “‘No dictator is inconvenienced or even displeased by cartoons showing his terrible person stalking through blood and mud… What he does not want to get around is the idea that he is an ass…”

Put simply, cartoonists keep politicians in their place. Their satire often punctures the aura of inevitability and authority that power depends on, returning political figures to the realm of the ordinary and the answerable.

Dave Brown, who has been a political cartoonist for the British online newspaper The Independent since 1996, put it plainly in an interview: “Political satire is an essential correlative to a functioning democracy…”

In India, multiple cartoonists have been taken into custody over political cartoons. Kerala Varma, better known as Kevy, spent time behind bars during the Emergency for cartoons that took aim at Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s regime.

Decades later, Aseem Trivedi – whose Cartoons Against Corruption campaign skewered political graft – was arrested in Mumbai in 2012 on charges including sedition, insulting national symbols, and posting “seditious and obscene” content. In 2017, Tamil Nadu cartoonist and columnist G. Balakrishnan, or G Bala, faced arrest for cartoons criticizing the state’s Chief Minister and local officials over their handling of a family’s self-immolation.

Others have been targeted. In 2020, a Supreme Court petition was filed against cartoonist Rachita Taneja, aka Sanitary Panels, accusing her of contempt proceedings for tweets criticizing the judiciary.

At the start of 2025, two other political cartoonists, Satish Acharya and Manjul, received notices from the social media platform X (formerly Twitter), stating that the Mumbai police had raised objections to some of their cartoons, which allegedly “violated the laws of India.”

“…political cartoonists are often the canaries in the coal mine, indicative of a democracy’s health,” Brown had noted. The canary, it would seem, is choking.

Related

The SIR’s Architecture of Bureaucratic Violence