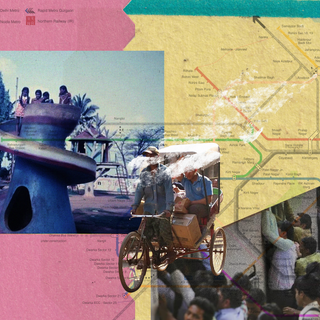

On January 19, nearly 50,000 people from Maharashtra’s Palghar district took to the streets, demanding the full implementation of an Act passed two decades ago. Led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist), the protest demanded full enforcement of legal safeguards for farmers and tribal communities, including the restoration of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and the effective implementation of the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996.

Among their key demands was the full implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) of 2006. For generations, forest laws had displaced Adivasi communities, criminalising their very existence on the land. The FRA was meant to reverse this.

In pushing back against a development system that treats forests as disposable, the Act reimagines forest ownership, shifting authority from distant bureaucracies to the communities that inhabit and steward them. Consequently, forest land can be treated as a shared commons.

The FRA, by design, endures across governments, codifying individual and collective forest rights and empowering gram sabhas to manage forests as living, self-sustaining ecosystems. Millions of FRA claims by forest communities have secured legal recognition and land-linked benefits.

Since the Act provides communities with a legal tool to defend their land and resources, it also makes many states wary. In Maharashtra and Odisha, delays and weak recognition of these rights continue to trigger protests.

Much conservation rhetoric positions humans as threats to wildlife, often weaponising this to evict indigenous communities. Inadvertently, it masks the true culprit: extraction.

With heatwaves, unpredictable monsoons, and raging storms, forests are central to India’s environmental survival. Their protection depends on recognising the people whose accrued stewardship could secure their future.