The SIR’s Architecture of Bureaucratic Violence

The Special Intensive Revision, pitched as a voter verification drive to purge “illegal immigrants,” gives the state room to redefine voter eligibility. Anyone it sees as unwanted are being pushed off the rolls.

I

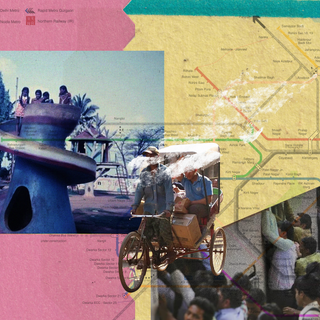

Sajida, 33*, lives in the ‘Bengali’ Basti, a sliver of tin-roofed jhuggi jhopris squeezed into a squalid corner of an otherwise orderly South Delhi neighbourhood of parks and gated apartments. In November, the Election Commission (EC) launched the second phase of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the electoral rolls, forcing Sajida’s parents into an unexpected, time-consuming trip to Cooch Behar, West Bengal.

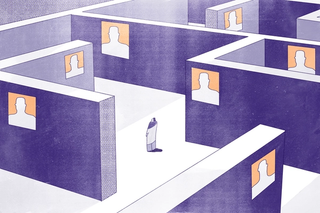

The SIR is a voter verification exercise the EC can trigger to update electoral rolls. This year, it was rolled out in nine states and three union territories – most of which are holding or heading into elections – and was framed as an “intensified revision” aimed at preventing the inclusion of “foreign illegal immigrants” on the rolls. In practice, it pushes poor, illiterate, and migrant voters – even those previously registered as voters – into a paperwork maze that is almost impossible to escape.

Here’s how the SIR works. A Booth Level Officer (BLO) visits a voter’s household with a pre-printed form carrying their details. The voter or a guardian pastes a recent photograph, checks the information, and updates key items: their date of birth, mobile number, and the names and Election Photo Identity Card (EPIC) numbers of their parents and, if applicable, their spouse. Those absent from the last SIR provide information about themselves or close relatives to link with the previous revision. The form is then signed, collected by the BLO, who certifies it and leaves an acknowledgement copy. Later, the details are digitised in the EC system to update the voter roll.

“Suppose my husband is labeled Bangladeshi. I am Indian. We have children. How will we live separately? We would have to leave India entirely."

It may sound routine, but for migrants like Sajida’s family, missing the enumeration form can mean losing their vote – even their citizenship. Living outside their registered constituency, they must travel home on time to fill the form, as online submission demands access and skills they often lack. Even when they make the journey, inclusion in the voter list is far from guaranteed. The EC notes that if an officer “doubts” a voter’s eligibility, “due to non-submission of requisite documents or otherwise,” they may be labeled a “suspected foreign national” and referred to “the competent authority under the Citizenship Act, 1955.” An exercise billed as simple housekeeping pushes the most vulnerable aside. Many do not have the documents to re-enrol, which leaves their vote and their citizenship in limbo.

“You know how it is in this country. For Muslims, especially, things are really hard,” Sajida told me one afternoon outside her shanty back in Delhi. “We have to keep all our documents ready and in order. You never know what might happen, or when.” For decades, Hindutva politics have turned the “illegal immigrant” – a euphemism for Muslims in India broadly and Muslims in West Bengal in particular – into an easy villain for its vision of a Hindu nation. Amit Shah once described the demographic as “termites.” The SIR is arguably the latest of several attempts to disenfranchise them.

“[Now] the burden of proof is on the individual to show they belong on the voter rolls."

“In Bihar, many people’s names got cut,” Sajida says, referring to the contentious first phase of the SIR, in which more than 65 lakh electors were removed from the rolls. “Now we don’t know what those people must be doing…” She adds, “Suppose my husband is labeled Bangladeshi. I am Indian. We have children. How will we live separately?” She nods at her twelve-year-old daughter, who hasn’t left her side since I arrived. “We would have to leave India entirely. That’s why, out of fear, everyone is going [home].”

Contemporary electoral bureaucracy, with its strict focus on forms and official documents, turns voting into a struggle for poor and marginalised residents like Sajida. As anthropologist Akhil Gupta writes in Red Tape, illiteracy turns bureaucratic writing into something “to be feared and avoided at all costs.” In Delhi’s bastis, the SIR turns the right to vote into a gamble.

II

The SIR itself isn’t a new electoral exercise, but its current execution stands apart.

Between 1951 and 2004, the SIR was carried out eight times, with the last exercise more than 21 years ago, in 2002-2004. For decades, intensive revision involved officials verifying new entrants door to door to uphold universal adult suffrage and maintain a reliable voter list. As academics Anupama Roy and Ujjwal Singh note in Election Commission of India, voters themselves had relatively little to do. Their role was largely limited to checking that their name appeared on the roll – not, as is the case in this year’s implementation of the SIR, proving that it belonged there. Indeed, this iteration is especially fraught, unfolding as increased worker mobility, population growth, and precarious urban migration in the 21 years since the last SIR put more people’s voting rights – and citizenship – on the line.

Gautam Bhatia, constitutional law scholar and author of Indian Constitution: A Conversation with Power, affirms that the SIR imposes a new hurdle for voters. “[Now] the burden of proof is on the individual to show they belong on the rolls,” he says. In a country where access to documentation is shaped by “axes of caste, class, gender,” this requirement is “onerous in many ways.” What sets the SIR apart, Bhatia adds, is that it creates a “second burden” on citizens simply to exercise their right to vote.

"A lot of people say 'Earlier, people used to elect their government; now the government is electing who is going to vote for them.'”

The pressure isn’t just on voters. BLOs face impossible demands of their own, an example of the structural violence Graeber describes, which creates “lopsided structures of the imagination,” forcing those with less power to expend energy anticipating the confused perceptions of the powerful, who remain largely blind to conditions on the ground. At least 14 BLOs reportedly died within three weeks, with families and unions attributing the strain to the exercise itself.

This sits far from the vision that guided India’s electoral system at its inception. When the Constituent Assembly envisaged the EC, it recognised that universal suffrage in a newly independent, postcolonial state would be anything but straightforward. At the time, it was a radical prospect – even Britain had secured universal suffrage only in 1928. As Gupta notes, there was almost no historical precedent for implementing such widespread voting rights in a country where literacy hovered around 30 per cent.

A 1951 article in The Hindu titled “Ensuing Election: Great Expectations” described India’s first general election as a “great experiment in democracy” and a “colossal” task. The scale was unprecedented, spanning over a million square miles and deciding roughly 4,500 seats. The magnitude of this exercise highlights how central the state was – and had to be – in building the electoral machinery from scratch. To ensure no eligible voter was left out, the EC held mock elections to train officers, introduced the symbol system for a largely unlettered electorate, and allowed displaced persons from territories that became Pakistan to join the rolls on oral declarations of intent to settle in India, as Roy and Singh note.

The traditional approach to preparing electoral rolls has thus always prioritised inclusion, with the state going to great lengths – even if imperfectly – to ensure all eligible voters were listed. Removing those later found disqualified came second. The SIR, however, flips this logic. Harshit Anand, a Delhi-based lawyer who practises in the Supreme Court and Delhi High Court, puts it bluntly: “A lot of people say, ‘Earlier, people used to elect their government; now the government is electing who is going to vote for them.’”

III

“See, the big people here don’t vote, they don’t care,” Sajida tells me. “But it matters to us.”

On top of the travel expenses, she worries the journey could cost her parents their jobs. Her mother cooks; her father works as a waste-picker. Employers don’t hesitate to replace migrant laborers, who already “find few opportunities,” as she says. In a city that treats such workers as disposable, finding new work is nearly impossible.

Under the SIR, workers like Sajida are forced to travel home to obtain forms from their BLOs and meet tight submission deadlines – an obligation especially taxing for this group. As anthropologist David Graeber notes in The Utopia of Rules, under total bureaucratization the less fortunate spend ever more hours negotiating increasingly elaborate “hoops required to gain access to dwindling social services.”

"If you’re a Bengali Muslim, they assume you’re from Bangladesh... Even though I have an Aadhaar card, a ration card, and a voter ID, they still claim I’m from Bangladesh.”

Sajida’s family relied on a literate neighbor to fill out the enumeration forms handed to them by the BLO. When the state shifts the burden of voter registration onto citizens, the most vulnerable – those without paperwork, literacy, time, or money – become the obvious casualties, notes Chittajit Mitra, General Secretary of the People's Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) chapter in Uttar Pradesh. Not only do they face the prospect of a lost vote; exercising their democratic right can now come at the cost of their livelihood.

The SIR process is particularly unforgiving for migrant workers. Anand adds that in West Bengal, long shadows of migration from the partitions of 1947 and 1971 mean many people – and their descendants – still lack proper documentation, leaving them exposed under the SIR’s exacting requirements, even if they have lived, worked, and voted in the state all their lives. In the years after Partition and Independence, mass migration and constant movement made questions of legal citizenship “fuzzy” or “indeterminate,” Roy and Singh note. Resettlement efforts fractured voting blocs into what critics call “hustled constituencies,” scattering populations across electoral rolls and leaving representation diluted to this day. The SIR only exacerbates these challenges.

“If you’re a Bengali Muslim, they assume you’re from Bangladesh,” Sajida tells me. “A man I used to work for would often say, ‘She’s from Bangladesh, not India.’ Even though I have an Aadhaar card, a ration card, and a voter ID, they still claim I’m from Bangladesh.”

The SIR gives the Election Commission the power to question a person’s citizenship – a power it does not legally hold.

Even after Sajida’s family submits the enumeration form, she says she won’t know if her name “made it onto the voter list or got cut” until she goes to vote next year.

The draft rolls go online this month. From 9 December 2025 to 31 January 2026, electoral officers are issuing notices to anyone whose name doesn’t match the last SIR, holding hearings, and allowing objections from those not on the list to decide who stays and who gets removed. “Right now, everything’s going okay enough,” Sajida said on the 22nd of last month. She added that it’s when the rolls arrive that “the real hungama (uproar) will happen.”

IV

Once the SIR wraps up nationwide, the fallout could be severe. The adult-to-elector ratio – which compares the number of registered voters to the total adult population – is now in the nineties, but it could slip into the low eighties or even high seventies. That kind of drop would leave up to a quarter of voting-age adults off the rolls, wiping tens of millions of eligible voters from the lists. The scale alone is enough to tilt constituencies and outcomes.

But the SIR presses on even as lawyers argue it breaches the Constitution.

According to Bhatia, erasing old voter rolls and starting from scratch is like saying, “because some people might be thieves, everybody has to deposit their keys with the local police station.” If the approach of exclusion first and verification later holds, Anand cautions, it could become the “new normal” of voter registration in India. On the political front, Rahul Gandhi called the SIR “a system to cover up the vote chori [theft] and institutionalise it.”

Critics have also called the SIR a “back-door NRC,” referring to the 2019 proposal that, as political theorist Niraja Gopal Jayal argued, "introduced, for the first time, a religious criterion as a test for citizenship" and set off mass protests nationwide. While there’s mixed consensus on this comparison, experts agree that the SIR fundamentally gives the EC the power to question a person’s citizenship – a power it does not legally hold.

If a person’s name disappears from the voter roll after the SIR, formal avenues for appeal exist. In practice, however, these mechanisms are hampered by the same constraints as the process of proving one’s place on voter rolls: limited awareness, scant resources, and tight deadlines. “Many people don’t even realise their names have been struck off until they reach the polling booth,” Anand notes. In states headed for elections – Bihar then, Bengal or Tamil Nadu now – revisions often occur so close to polling that any final remedy becomes meaningless.

Although Sajida and her friends have worked in Delhi for over a decade, they tell me they have seen little of the city beyond its major landmarks. They laugh at the absurdity of the idea that they ever might. There is neither time nor money for recreation, or for ghoomna (going out for fun), as they call it. “We have to earn our living by working. If we don’t work one day, there won’t be any food in our stomachs the next.” Like Sajida told me, you never know what might happen, or when. She highlights an impossible bargain: the right to vote, or the right to a livelihood? With the SIR, some people are forced to choose.

I asked Sajida what she thinks the future holds for this country. “Modi-ji will drown the entire world. He drowned us in debt already; now he will drown people too...” Those spared might keep afloat for a while, until the bureaucratic quagmire swallows them too.

Diya Isha is Associate Editor at The Swaddle and a National Book Critics Circle Emerging Critics Fellow. She can be found on Instagram at @contendish.

Related

The Utopia of the Livable City