Death Penalty for Child Sexual Abusers Is Not a Good Idea

Mainly because it won’t solve the problem.

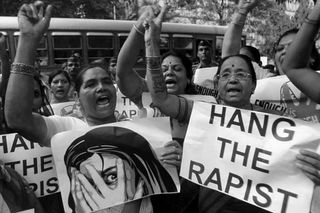

On Saturday, the BJP held an emergency Cabinet meeting in response to protests over the rape of a minor in Unnao, Uttar Pradesh, and the rape of an 8-year-old in Kathua, Jammu. During the meeting, the Cabinet approved an ordinance that introduced the death penalty as punishment for the rape of children under 12 years old.

It’s not a surprise decision; numerous Union Cabinet members have advocated for instating the death penalty as pressure mounted from the public – a good proportion of which led the charge toward capital punishment. Hashtags such as “HangKathuaRapists” and “DeathPenaltyForRapists” have been circulating on social media. A Change.org petition calling for the death penalty for the Kathua rapists received more than 100,000 signatures.

But the ordinance won’t solve the underlying problem, and most importantly, won’t prevent this from happening again. This ordinance is a stopgap measure that will likely cause more harm than good, an ostensibly condemnatory maneuver aimed at silencing protests while doing nothing to actually address the current cultural milieu that has led to these crimes, or to prevent child rape in the future.

To the first point, the government is using the death penalty to distract from what both crimes actually call for: outright condemnation of members and belief systems within its own party. This is especially true for the rape and murder of the 8-year-old in Kathua, identified by the press as Asifa, which was not an act of pedophilia alone, but perpetrated for political reasons, part of a communal plot to put local Muslims ‘in their place.’ It was an act of terror, a hate crime perpetrated by members acting on behalf of the Hindu nationalist community. (Currently, religion-based hate crimes are punishable by up to three years in prison – up to five if committed in a place of worship.)

To the second, the punishment ignores basic, incontrovertible facts about both the death penalty and child sexual abuse.

Countless studies and statistics show that the death penalty is not an effective deterrent. In fact, 88% of criminologists believe that the death penalty has little overall effect on preventing people from committing a crime. While a global majority still believes in the death penalty, moral tides are beginning to shift away from it, and more countries are moving to abolish capital punishment altogether.

With this move, India is taking a step in the wrong direction – because it misses the basic facts about how and why most child sexual abuse is perpetrated. Forty percent of child sexual abuse is perpetrated by older children, and the majority at the hands of known people — family and friends.

As it is, these crimes are going underreported. Children are afraid of reporting an uncle, brother, cousin, or teacher, because when they do, they are either silenced or face repercussions themselves. This insidious silencing will only worsen if the consequence of reporting a family member is their death sentence.

Punitive justice such as capital punishment may help provide some solace to survivors, victims’ families, and a still-reeling public. The Kathua girl’s mother had called for the death penalty, and the girl’s father expressed hope, yesterday, after hearing about the new ordinance.

However, this form of justice feels like a symbolic and hollow victory. Punishment may make the Kathua family feel avenged in the short term, but the only thing that will truly honor the child’s memory is channeling this surge of public grief into something that will prevent the next child from becoming a victim in the first place – and it’s pretty clear that the death penalty won’t do that. It’s also pretty clear that instating the ordinance wasn’t even an attempt to do that.

Unequivocally condemning the divisive politics behind the heinous act in Kathua and publicly shunning the accused BJP MLA in Unnao would have been a better start. Requiring all elected politicians and members of police to undergo gender sensitization training would be a second step. Saturday’s ordinance called for forensic ‘rape kits’ to be placed in police stations and hospitals, but there also needs to be accompanying legislation ensuring that victims can report rape without being further traumatised by victim-shaming, victim-blaming, and outright dismissal, as is too often the practice currently. Additionally, police should be compelled to investigate any rape allegations, regardless of who the accused is — be it a family member, a politician, or someone from within the police’s own ranks. Finally, instituting sex education and gender sensitization classes in all public and private schools would give children the vocabulary, understanding and confidence to report crimes against their bodies.

As a country, the Kathua and Unnao rapes, as well as others, have left us shocked and outraged, and consequently, we seek justice. But the decision to reinstate the death penalty for child rape should make us question the manner in which we achieve that justice. Is the right course a measure that will punish a handful of rapists while doing nothing to dismantle the culture that silences victims? Or is the better approach a less immediate and satisfying one, but which ultimately may prevent more crimes like this one? This may feel like an impossible choice, but it doesn’t seem like an exaggeration to say that it’s one we must urgently answer.

Related

Canned Food Packaging May Disrupt Nutrient Absorption