On 'Newstrack,' or Digital News Before Digital News

In retrospect: A video magazine that set the template for Indian news media today. Before digital news pundits, there was Newstrack.

'In Retrospect' is a look at cultural predecessors that were ahead of their time, for better or for worse.

Long before the Internet became a haven for alternative news, with laws racing to keep pace with its indefatigable advance, journalists working around the strictures of analogue media were already outflanking the state. In the late 1980s, Newstrack turned to video cassettes to circumnavigate the Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act of 1933, which made any private broadcast illegal. By using a novel medium to sway audiences directly, Newstrack anticipated the provocations of today’s digital media, where governments are scrambling to regulate “alt” news online and curb what they sometimes misguidedly call misinformation.

The year was 1959, and there was only one thing to watch on Indian television: Doordarshan, the state-controlled broadcaster. Like Adam biting into the apple, the average Indian – or at least ones who owned a TV – huddled in front of the new medium, thoroughly beholden, helping to build a nation imagined by the state, their only input passive consumption.

For three decades, DD sat comfortably in its role as a mouthpiece for the state, presenting a sanitized, idealized image of India. And then, the rupture: the disclosure of a scandal that cost the Indian National Congress the 1989 general elections. With corruption at the highest levels of government exposed, the spectre of the perfect nation being broadcast on DD could no longer coddle the consumer.

In time, like any consumer, Indians turned weary, discontent with the monopoly. There were many newspapers, so why could they not have more channels? The visual medium of television possessed a potency that the written word could not rival, especially in a country enamoured by the possibility of cosmopolitanism. Journalists eventually found a loophole: Although the state controlled the airwaves, it could not control the distribution of other analog media, marking the advent of video magazines.

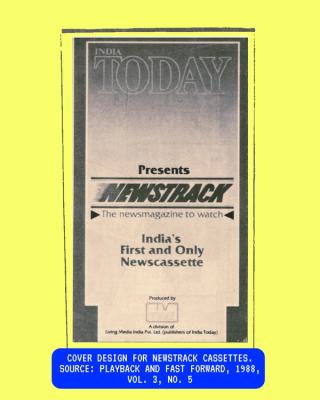

Video magazines were already popular at this point, as a novel form of entertainment periodicals, covering the likes of star interviews, behind-the-scenes footage, music launches, and soirées. But Newstrack, launched in early 1988, introduced India to the format of a video news magazine, focused on current affairs. Far from being an underground experiment, Newstrack was backed by India Today, which gave it both credibility and distribution muscle. Its video cassettes were available to rent both through its sister publication as well as in video libraries across the country, even negotiating with courier companies so that some issues reached subscribers sooner based on their “news value”.

Newstrack’s novelty lay less in its anti-establishment bravado than in its format – news reinterpreted as a commodity, rented and circulated through the same channels as popular films. In a 1988 piece entitled “Video Magazines: The Medium is the Message”, the journal Playback and FastForward wrote, “The effect of the video medium will be felt thereafter by DD, promising some improvement in TV.”

Newstrack’s deployment of close-ups, jittery camera movements, and rapid montages engineered a sense of immediacy and “liveness” that sharply juxtaposed the polished, regimented static-camera aesthetic of Doordarshan’s news broadcasts. “The material infrastructure of Newstrack helped craft a visual grammar that was distinct from state television,” writes Ishita Tiwary in her book, Video Culture in India: The Analog Era. The audience craved something more alluring, less staid. “Information-hungry Indians, annoyed by the failures of state-run broadcasting networks, are turning in droves to private-enterprise ‘alternative television’ news on videotape,” wrote The New York Times in 1991.

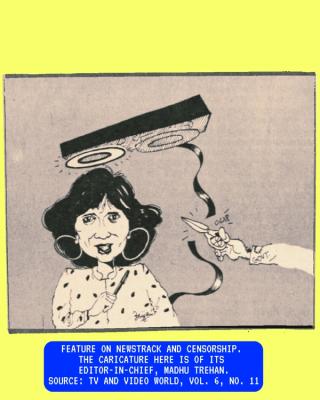

Even as it positioned itself against Doordarshan’s prissy monopoly, Newstrack never quite became the radical outlier it was imagined to be. Through its model of presenting “alternative” news via non-traditional formats, it flouted the cardinal rule of “news”: checks and balances. Its affiliation with established media house India Today tethered it firmly to the mainstream. Instead, what it sold the masses was the appearance of standing apart, a comportment of provocation that carried cultural capital in late-80s India, when appearing anti-establishment had itself become a kind of establishment chic.

When covering the often violent and disruptive anti-Mandal protests, Newstrack primarily amplified perspectives critical of the commission's implications, giving less airtime to those who supported reservations. The fact that the magazine was heavily censored only fortified its appeal to the otherwise tame urban viewer. In 1991, broadcasting became legal, and Newstrack closed up shop, having already shifted from a video magazine critical of the state to an hour-long news programme on Doordarshan, leaving the country’s media landscape permanently altered. One year later, Zee TV launched as India’s first private satellite television channel. Private production began diverting audiences, gradually exerting influence over state-run broadcasting.

While the audience for news swelled, so did their appetites. By the 2000s, India witnessed the rise of 24-hour news channels. And by 2012, the proliferation of cable and satellite channels had produced over 400 news and current affairs outlets.

As the once decorous airwaves flooded with private satellite and cable channels, 24-hour newsrooms, and conglomerate-owned networks, Newstrack’s then-edgy theatrics were cheerfully commercialised by the market. Actorly voiceovers and sensational visuals soon became standard and expected across every prime-time news slot on major channels. To rake in TRPs, everything was made urgent and personal. Like when a news channel undertook the solemn task of fact-checking the breadth of our prime minister’s chest after an opposition leader suggested he wasn’t a fit politician for lacking a chhappan inch ki chhati (56-inch chest). News and narrative became inseparable.

Soon, some alt media outfits too began adopting the modus operandi of Newstrack, which was not to offer the prim and proper news of the imagined heydays but to make sense and offer opinions on current affairs. News websites like OpIndia exemplified this approach: Partisan, sensationalist, and selectively factual, it swiftly dismisses opposing perspectives and panders to its audience’s preconceptions.

Today, although not everyone has a television, almost everyone has a smartphone, a brand-new distribution channel for selling phantasms at an astonishing pace. This became possible in 2016, when the launch of Reliance Jio disrupted the telecom market with its affordable 4G data plans. News – or at least the pale imitation of it – suddenly became even more economical to produce.

The result? Social media platforms teem with “deep dives” and “explainers.” YouTuber Dhruv Rathee is celebrated for swaying the public against the BJP. Podcasts full of pontificating men come to be seen as either subsidiary to or autonomous from Big Media, which is understood as honour-bound to the Establishment. Even the government, with all the accusations of running a quaint apparatus, launched the National Creators Award to recognise digital content creators, as if to menacingly assure us that they are watching everything on the Internet, even as all the digital platforms dash to persuade us that no one is. Of the many independent news organisations, some curate what is already public, others break new ground, some turn reportage into narrative, and others pare it back to facts.

With a legion of platforms and competing narratives, the audience now is once again left to speculate. When so much of the media landscape positions itself as alternative, who actually is?

The question of what “alt media” is depends entirely on where you stand. What counts as alternative for some is mainstream for others. And so, what qualifies as “alt media” is whatever barters with your politics and the narratives you already trust. A paper’s political agenda cannot be distinguished from that of another unless examined closely. The mongers of misinformation rely on the fact that few do.

The title of “alt media” permitted an existence in ambiguity that Newstrack could afford because its consumers were self-victimised, English-speaking, middle-class Indians. But the democratisation of media and its many avatars multiplied that ambiguity, making it easier for alternative mediums to camouflage their respective agendas. What follows is not only a cautious suspicion of legacy media but also of whatever presents itself as alternative. The medium, it might seem, can no longer be entrusted to carry the message.

Diya Isha is Associate Editor at The Swaddle and a National Book Critics Circle Emerging Critics Fellow. She can be found on Instagram at @contendish.

Related

Who Goes on America’s Watchlist?