The Cult of the Teenage Messiah

How the world turned Malala Yousafzai into a brand of hope while letting real change slip by.

When the world bet on Malala Yousafzai to single-handedly solve the problem of women’s empowerment, it perhaps even seemed possible. Today, the men who nearly succeeded in murdering her are feted as a legitimate power. They hold press conferences, walk shoulder to shoulder with heads of government, and are more influential than ever, courtesy of the same Western world that once valorised their sworn girl-enemy.

The teenage messiah was how the world outsourced its conscience, and Malala Yousafzai was its most perfect expression. Her story is not only about a girl who survived an attempted assassination and became a global icon, but about the mechanisms through which the powerful maintain their image while real change remains elusive.

“I had choices that millions of young women had just lost,” writes Yousafzai in Finding My Way. At twenty-eight, she has already written two memoirs. “To agonise over my place in the world seemed immaterial,” she insists. All her life, her work as a teenage messiah has allowed her to do little else.

Yousafzai does see the irony. She knows her presence is regarded less as that of a person and more as that of a figurehead: “If I wanted to promote education and equality for girls and women in Pakistan, I had to be inoffensive in every way,” she writes, weary of the saintliness expected of her. What goes unmentioned is that this very symbolic virtue is what first lionised her.

Yousafzai, who once cited Obama as an inspiration, was doomed to mimic him, to the point where the Malala who had audaciously questioned the president on his drone warfare policies is all but a spectre.

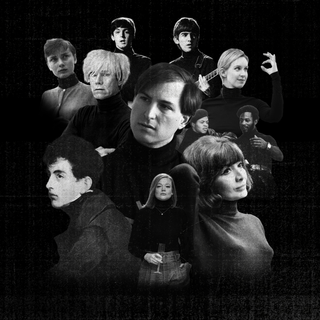

At the time Yousafzai became a household name, teenage messiahs were impossible to miss. Whether it was Katniss Everdeen of The Hunger Games or Beatrice Prior of the Divergent series, the messiah was always a young, hapless teenager, saving the world after an inopportune encounter with kismet. In the 2010s, their plaintive portraits doled out hope to all, their speeches emphatic, punctuated by ovations. A fixture of popular culture, fictional teenage messiahs spawned several multi-billion-dollar franchises. Inadvertently, they also charted an archetypal path Yousafzai seemed fated to follow. “The pressure built inside me…” she mulls, her writing carrying the restless urgency of a teenage hero brought to life. “I started to believe that I was personally responsible for delaying progress.”

Even as Yousafzai internalised the burden of progress, others were eager to project it. In Barack Obama’s famous White House photo-op with her, he hawked his brand as the president with the “audacity of hope.” As Naomi Klein observes, after the Bush years – marred by the blunders of the war on terror – a change of self-image had become a necessity for Obama and a “battered” America. He embodied, as she puts it, a “preference for symbols over substance.”

A few months after Obama secured his second term, Yousafzai stood on the cusp of global renown, addressing the United Nations on her 16th birthday. The two would prove to have much in common. In an age of political paralysis, they were paraded as progress itself, even the extraneous bits of their celebrity. After all, Yousafzai, who once cited Obama as an inspiration, was doomed to mimic him, to the point where the Malala who had audaciously questioned the president on his drone warfare policies is all but a spectre.

American Pop Culture Is American Empire

Yousafzai’s brand as the teenage messiah, in being a brand, has an in-built prerogative to capitulate to what scholars describe as “affective politics.” For the public, it is easy to mistake the promise of progress for the achievement of progress. As the America-orchestrated wars in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Syria raged on, Yousafzai’s rise offered the West a symbolic Muslim heroine – a gentler face of the same order. The teenage messiah, a token of hope in a landscape slowly growing more suspicious of Obama’s politics, helped mask the need for a broader civil movement.

For the adults with power, the messiah’s gullible belief that they could change the world was excusable, even welcome. Anything else would’ve forced Yousafzai to see, as she now does, that it was all little more than “photo ops” for governments and media eager to look progressive as they co-opted their trauma. After all, there’s no better brand than an accidental one, one that never seeks the fame it is eventually afforded.

Yousafzai, an activist long before she was shot, signed the paperwork to set up the Malala Fund from her hospital bed, still recovering from her injuries. The NGO would, she hoped, “redirect all the attention [she] received into helping other girls go to school.” In practice, the humility celebrated in the NGO‑industrial complex often doubles as a branding strategy. The Malala Fund was no exception. As political theorist Neera Chandhoke noted, “people struggling against authoritarian regimes had demanded civil society; what they got instead were NGOs.”

In her memoir, Yousafzai admits that sometimes she does not think she has advanced her goal. This is probably because NGO-isation presumes that liberation is quantifiable.

In her essay, “The NGO-ization of Resistance,” Arundhati Roy writes, “As the state abdicated its traditional role, NGOs moved in to work in these very areas.” When an activist like Yousafzai becomes part of the machinery, her conscience too must learn to clock in and out. A corporate culture devoted to reform rather than revolution can’t contain the ambit of a radical’s goals. With NGOs, liberation could be compartmentalised into more “achievable” goals, as, for instance, girls’ education or sustainability.

Within this context of governance, Yousafzai became one of the poster children used to prop up the fiction of Western benevolence. At the time, Western feminism was transforming into “an ally of the new world order and the new imperialism which [used] the language of women's rights to protect their strategic interests,” writes Nivedita Menon in Seeing Like a Feminist. Soon enough, every ethno-nationalist conflict, whether in the Balkans, Afghanistan, or Iraq, was reconceptualised as “a war against women” in Western media.

In most cases, Menon notes, these NGOs have little or nothing to do with the local movements in the countries they are trying to help. This volitional detachment explains why NGOs are attracted to seemingly straightforward projects like women’s education in these volatile countries. What makes such projects even more dubious is that, although education is often treated as secondary to civil and political rights in the West, it becomes a charged, politicised mission abroad. When framed as a means of liberation, women’s education is invoked much like the rhetoric once used by imperial powers to justify intervention in “developing” nations. This approach obfuscates the reality of what is actually happening in those countries, where the material, economic, and political conditions that constrain women’s lives are systematically neglected and often worsened by foreign involvement.

We Have to Retire the Phrase ‘Women and Children’ in Conflicts

In her memoir, Yousafzai admits that sometimes she does not think she has advanced her goal. This is probably because NGO-isation presumes that liberation is quantifiable. In relying solely on statistics to mark progress, welfare-adjacent services forget that numbers can only tell part of the story. But Yousafzai’s modesty in her book precludes self-awareness. Almost defensively, she tallies her achievements like entries in an NGO report, including the accolades that are suspect. When she hails Apple for funding schools in Brazil, Nigeria, and Pakistan, she leaves out the girls mining for cobalt for iPhones from her tale of empowerment. For companies like Apple, an alliance with a teenage messiah is good business. By pedestalising her and her many corporate-feminist ventures, the West reattains its status as emancipator, even as an imperial power.

In over a decade of her career as a teenage messiah, Yousafzai has acquired an impressive litany of honours: the Nobel Peace Prize, an Oscar-nominated documentary about her, multiple features in TIME’s list of the world’s most influential people and, most triumphantly, a ban on her memoir in Pakistan.

What makes the teenage messiah so compelling is that, in recognising her as a godsend, we assure ourselves of our goodness. In recognising her fall, we do so doubly.

Her (second) memoir arrives against the backdrop of her relative silence on the genocide in Gaza, contributing cheerfully to a mainstream news cycle long disinvested in calling a spade a spade. By platforming her with renewed energy, the Western world looks busy fixing itself while reproducing the very hierarchies that make the Malalas of the world necessary. She fits deftly, even conveniently, into what the neoliberal order expects a liberated Muslim woman to be: grateful, accomplished, and politely assimilated.

Although her memoir reads in the style of a coming-of-age novel, where conflict gives way to resolution, the battles Yousafzai has chosen are far from over. If she were, in fact, the protagonist of such a story, her settling into a happy marriage, attending the Oscars, and appearing in Vogue with her husband as the world burns would read as a turncoat ending.

What makes the teenage messiah so compelling is that, in recognising her as a godsend, we assure ourselves of our goodness. In recognising her fall, we do so doubly. Perhaps Malala’s decline began with attempting to perform relatability. Messiahs, unfortunately for her, are not meant to be relatable; they must appeal to a standard higher than you or me. When they are found wanting, it unsettles our own discernment – our choice of prophet – as seen in the barbs that flood Yousafzai’s tone-deaf, cheerful social media posts.

We created the teenage messiah so we could believe that goodness could be outsourced. To love Malala is not to stand up for all the Muslim women wronged jointly by their own communities and the West. It is to endorse a brand.

Diya Isha is Associate Editor at The Swaddle and a National Book Critics Circle Emerging Critics Fellow. She can be found on Instagram at @contendish.

Related

Bad Men in Armani Suits