How We Loved and Lost the Black Turtleneck

In retrospect: A garment's transition from chic to Silicon Valley.

'In Retrospect' is a look at cultural predecessors that were ahead of their time, for better or for worse.

You are the most mysterious when you wear a black turtleneck. Immortal, a uniform without being a uniform, it projects whatever mythology the wearer demands: brooding artist, disruptive tech visionary, radical intellectual, fashion minimalist.

In a 2015 interview with Glamour, three years before she was indicted for wire fraud, Elizabeth Holmes claimed to own at least one hundred and fifty black turtlenecks – fifty more than Steve Jobs. Her effort at self-mythology included divorcing her style from the assumption that it was inspired by Jobs: “My mom had me in black turtlenecks when I was, like, eight.” Holmes was meant to appear a prodigy, but her insistence only marked her as an over-eager aspirant, lacking the effortless cool of her predecessor. While the world was shocked by her lies about a technology too good to be true, the world also belatedly admitted to having feigned credulity. In the end, the black turtleneck became implicated in the charade itself.

Long commiserated in Renaissance Europe as a colour bereft of vanity and suited only for monks and mourners, black soon earned praise for its ability to “[enhance] the individual qualities of the human face,” as Anne Hollander notes in Seeing Through Clothes. But the story of the turtleneck began long before Holmes or Jobs. According to English novelist Evelyn Waugh, everyone at Merton College, Oxford, was wearing a turtleneck in 1924. In his diaries, he describes this “new sort of jumper with a high collar” as “most convenient for lechery,” its high neck sparing the wearer from further styling with “studs and ties.” Like most modish clothes of the time, the garment was best worn in black.

But even back in the eighteenth century, Lord Byron made his all-black evening dress the prerogative of the fashionable, brooding man. Dracula, the Gothic psychosexual nightmare of the Victorian era, could not be imagined in anything but the livery of this Byronic figure. Black high-necks, both flamboyant and understated, also brought a crooked twist to Dandyism. It was agnostic of class and status; it wore the wearer.

By the late 1940s, after the Second World War, the turtleneck – commonly worn by fishermen, manual workers, athletes, sailors, and naval officers – attained immortality and greater cultural cache when Parisian Left Bank intellectuals adopted it. High-necked and black-knit, the turtleneck shaped its wearer into a withholding thinker, the neckline framing the face and making their alertness – and suspicion of others – immediately apparent. It became the androgynous choice for feminists and the purportedly emasculating, form-fitting option for queer people, activists, and the general who’s who of the class that took on what Tom Wolfe called “radical chic.” Everybody, then and now, wanted to look like James Baldwin in that one portrait or like Michel Foucault, whose silhouette was instantly recognisable and reproducible thanks to the signature garment.

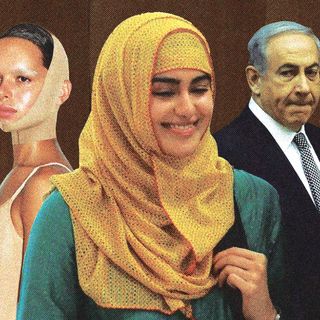

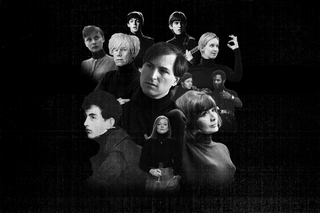

Anybody who was anyone wore it, and they wore it especially when being audacious. Bob Dylan, as he made the contentious leap from folk to electronic music. Andy Warhol, trading his pre-fame preppy suits for his trademark quirky, avant-garde style. Lou Reed, when he and The Velvet Underground were discovered by Warhol. Marlene Dietrich, as she became the scrummily brazen bisexual of the stodgy American film circuit. The Black Panther Party, as they railed against the gullibility of a nonviolent racial justice movement. Deepika Padukone, when she stood with students at Jawaharlal Nehru University during the anti-CAA protests.

The New York Times reported in 1967 that turtlenecks had become “as inescapable in Manhattan as air pollution,” and that “the longtime turtleneck wearer often [began to feel] he's just as much a conformist as the shirt-and-tie man.” The turtleneck’s ambiguity was amplified by the fact that it had been embraced both by Jackie Kennedy, the embodiment of elegance, and Marilyn Monroe, the epitome of Hollywood glamour. Nothing was more versatile, offered more range, and was at once ubiquitous and subversive. Not to mention sexy.

The Beatles often paired their turtlenecks with bespoke jackets or jeans, a combination that was hardly novel. But what mattered less was what the turtlenecks did for the Beatles and more what the Beatles did for the garment. And so, through its repeated, persistent association with iconic renegades, the black turtleneck maintained its place in fashion, while simultaneously being garden-variety.

When culture gave way to the information revolution — itself an unlikely and eventually bastardized offspring of 60s hippie counterculture — it was inevitable that its progenitors also adopted the uniform of non-conformist innovation. And so a contemporary discussion of the black turtleneck is incomplete without the lore of Steve Jobs. In the early 1980s, Jobs wanted his employees to wear an Issey Miyake-designed uniform, like the factory workers at Sony, to help them bond. They booed at the prospect, he told Walter Isaacson, his biographer. Like a techie Mao, he instead chose a uniform for himself, asking Miyake to reproduce the most banal of his designs for this endeavour. Miyake obliged, filling his closet with black sweaters built to last a lifetime. From then on, Jobs almost never appeared without what became his signature style, which came to symbolise the disciplined but maverick genius. Apple products, Jobs implied by emulating their minimalist aesthetic, were for serious people who had no time to loaf. Through his personal style, Jobs wanted to project Apple’s philosophy of pared-down, no-fuss design.

Jobs' personal discipline paralleled a wider cultural shift. The black turtleneck epitomised what English media theorists Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron called "The Californian Ideology," which “…simultaneously reflects the disciplines of market economics and the freedoms of hippie artisanship.” This ideology became inescapable in a neoliberal market where Silicon Valley abruptly annexed Wall Street, forcing the jocks of yesterday to appeal, often humiliatingly, to the nerds of yesterday. The nerds were, in turn, political co-opters of their flower-power predecessors. Eventually, the black turtleneck turned into collateral damage: a piece once associated with radical intellectuals found it difficult to remain cool once tech overlords masked their neoliberal schemes in the guise of revolution. Almost as if to say that wearing the black turtleneck is a sign of being cavalier. About caring for the tech and not what “they” – those moneyed idiots – thought. Even if the long con was trying to become the moneyed one yourself. When Elizabeth Holmes chose the black turtleneck as her uniform to hawk a product she knew didn’t work, she was projecting precisely this insouciance.

Today, the black turtleneck is the stuff of corporate and political satire-dramas. Shiv Roy can often be found wearing one, as can Emmanuel Macron and Vladimir Putin. To call it a uniform is almost a snub, considering that most who wear it do so with a certainty of their singularity. The black turtleneck no longer surprises, nor is it radical. Its biggest con? Convincing us that wearing it is an act of personal taste.

Embers of the black turtleneck’s insolent past persist in fast-fashion retailers and various “-core” trends (read: “dark academia,” courtesy of the TikTok-ification of Donna Tartt’s fiction). If we’ve learned anything from the garment’s longevity and its various evolutions, it’s that conformity and individuality are not mutually exclusive in a neoliberal world. The garment’s ability to manifest both uniformity and personal expression has turned it into a ritual that feels more familiar than radical or interesting. And we’re all worse off for it. The black turtleneck is dead; long live the black turtleneck.

Diya Isha is Associate Editor at The Swaddle and a National Book Critics Circle Emerging Critics Fellow. She can be found on Instagram at @contendish.

Related

Will Thirst Save Our Democracy?