'Vestigial' Organs, and Other Lies About Our Bodies

Declaring any part of the body “useless” is not just scientifically premature, it is philosophically cruel, because it reduces creation to mere utilitarianism and erases the possibility of layered meanings.

In 11th grade, when my teacher drew parallels between the liver and a factory, I was awed by the elegance and purpose embedded in the human body. The analogy prompted a sense of wonder — a sensibility that has largely been stripped away in modern science, which trains us to see in fragments.

We teach the heart without thermodynamics, the lungs without physics, immunity without ecology. But the body doesn't work in silos; it's our inherited education system that builds silos around it. When teaching, medicine, and healthcare adopt a fragmented approach, they inevitably promote questionable ideas like vestigiality and reductionism. Sans a holistic framework, we reduce the body to merely its components, overlooking its hidden wisdom.

This tendency to see organs as isolated machines extends beyond the classroom and healthcare – it shapes our culture’s relationship with the substances that sustain life, such as fat. Fat, a word spoken with the same disdain as "poison," has been vilified in modern culture as waste, excess, or pathology. Yet, the mesentery, critical to our functioning, is mostly made of fat. Its role in upright posture, organ suspension, and immune protection suggests that fat is not incidental but structural and intelligent. The very nutrient demonized in diet culture sustains us in hidden ways. Dietary fat, demonized in low-fat popular culture, has now been rediscovered as essential for the brain, hormones, and vitamins.

Since the first systematic review in 1978, decades of studies have confirmed that dietary lipids are not passive calories, but active participants in immune regulation. The cultural demonization of fat as though it were only “clog” and “excess” is thus shallow. Even the cholesterol found in arterial plaques may not be random villains, but first responders – they rush to sites of vascular injury, attempting repair. The tragedy of a heart attack, then, may not be fat’s malevolence but its failed rescue mission, overwhelmed by chronic inflammation and imbalance. To accuse fat is like blaming the firefighter for the blaze.

Yet the legacy of this vilification runs deep, creating modern-day rituals of avoiding natural fats, which are as fervent as they are nutritionally misguided. For instance: the ritualistic discarding of the egg yolk from a boiled egg as if it were a toxin. This bright yellow centre – a powerhouse of choline for the brain, fat-soluble vitamins, protein phosvitin (which works to reduce inflammation), sulphated glycopeptides (which stimulate the production of immune cells), and essential fatty acids – is meticulously carved out and thrown away. It is a testament to how completely a simplistic, villainizing narrative can overwrite centuries of traditional wisdom and modern scientific understanding, creating a public health tragedy – one discarded yolk at a time. Most experimental, clinical, and epidemiologic studies have concluded that there is no evidence of a correlation between dietary cholesterol in eggs and an increase in plasma total-cholesterol.

Just as fat has been unfairly maligned, the idea of vestigiality has also been eagerly propagated. To dismiss the appendix, coccyx, auricular muscles, or wisdom teeth as “useless leftovers” is to ignore history: Every decade, yesterday’s “useless” tissues are discovered to have subtle functions in immunity, mechanics, development, or adaptation.

The same goes for ghee, indigenous to India and revered for its nourishing and energetic properties, it has been a cornerstone of Indian cuisine and medicine for millennia. Its richness and “greasiness” are frequently equated with indulgence, weight gain, and disease. Yet, ghee is far more nutritionally sophisticated than hydrogenated oils or processed fats. To cast it as “villainous” is not merely a dietary error; it reflects a cultural shift from nuanced, empirical knowledge to reductive, fear-driven paradigms.

Nearly 60% of the brain is lipid and, in toddlers, this dependency is even sharper: During the first two years of life, when the brain triples in size, adequate fat intake determines the very architecture of cognition. Breast milk, remarkably, is rich in these lipids, nature's way of ensuring that thought itself is scaffolded by fat. That is, without fat, memory, learning, and intelligence cannot be built.

Just as fat has been unfairly maligned, the idea of vestigiality has also been eagerly propagated. To dismiss the appendix, coccyx, auricular muscles, or wisdom teeth as “useless leftovers” is to ignore history: Every decade, yesterday’s “useless” tissues are discovered to have subtle functions in immunity, mechanics, development, or adaptation.

Moreover, declaring any part of the body “useless” is not just scientifically premature, it is philosophically cruel, because it reduces creation to mere utilitarianism and erases the possibility of layered meanings.

Large portions of DNA, introns, transposons, and so-called “junk DNA” for instance, were long dismissed as useless leftovers. However, research over the past two decades has shown that these sequences regulate gene expression, maintain chromosomal architecture, and even influence development and immunity. The very signature of our life has been misjudged simply because we lacked complete information. Even the appendix, which was long cited as prime evidence of evolution and the existence of vestigial organs, is now understood to play a role in immunity.

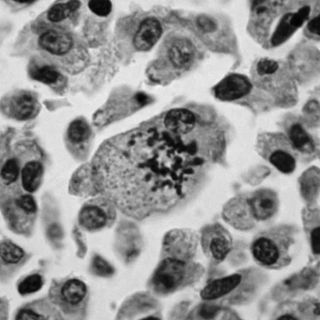

The rete ovarii (RO) is another example of how “vestigial” is often a synonym for ignorance. First described over a century ago, the RO was labelled as being vestigial and having no clear purpose. But new research in mice reveals something very different: Surrounded by nerves and vessels, the RO’s function may be to integrate signals across systems once thought separate. If confirmed in humans, the RO could redefine our understanding of fertility and ovarian function.

That this revelation comes from the female reproductive system is telling. Historically, women’s health has been under-researched and under-funded. Animal models of female reproduction are costly and complicated by hormonal cycles. Clinical research often excluded women for fear of “complicating” results. The result: scandalous medical oversights, from thalidomide prescriptions in pregnancy to the continued underdiagnosis of endometriosis.

To view the body solely through the lens of utility is to miss the subtle orchestration, the interwoven capacities, and the profound potential encoded within each organ—capacities that traditions across cultures have recognized long before modern science reduced them to “function.”

We know so little of the female body because we have chosen to know so little. The RO, like the mesentery before it, calls us to wonder. The body is not a museum of relics but a manuscript whose margins continue to reveal fresh glosses.

In Kashmir, the uterus is sometimes called the b’oon of the body, a metaphor drawn from the chinar tree, suggesting its might, strength, intrinsic value and sheltering nature. Yet, despite the significance of the uterus’s role transcending the physical act of gestation, it is treated with striking indifference in clinical practice, often removed with a callousness that belies its majesty and power.

Hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus, is among the most common operations performed on women worldwide. Nearly one in four women in the United States undergoes it by the age of sixty; in India, the National Family Health Survey reports that about 3–6% of women aged 15–49 have already lost their wombs, with some states reaching as high as 10%.

By contrast, surgeries involving removal of male reproductive organs are astonishingly rare; orchiectomy, for example, affects fewer than 0.1% of men and usually only as a last resort for cancer. The asymmetry is striking: women’s reproductive organs are routinely excised even for benign or manageable conditions, while male reproductive structures are culturally and medically guarded with near-sanctity.

Just as fat was demonized despite centuries of empirical and traditional knowledge, the female body has suffered from a similar epistemic neglect, a testament to the dangers of fragmented understanding.

To view the body solely through the lens of utility is to miss the subtle orchestration, the interwoven capacities, and the profound potential encoded within each organ—capacities that traditions across cultures have recognized long before modern science reduced them to “function.”

Across ancient traditions, the very notion of a “vestigial” organ would have sounded absurd. In Egypt, each organ carried afterlife significance: the heart was weighed as the seat of conscience, the lungs, liver, and stomach preserved in canopic jars, while even the brain (once discarded by embalmers) was not thought meaningless, but mysterious. Islamic physicians, heirs of Galen and Aristotle, infused anatomy with theology: Ibn Sina rejected the possibility of useless parts, arguing that divine wisdom (hikma) leaves nothing in vain, echoing the Qur’an’s reminder that “you are given of knowledge only a little.” Even Aristotle himself, centuries earlier, had insisted that “nature does nothing in vain.”

In the end, what is most striking is not the new discoveries about the roles of organs, but the audacity with which we once dismissed what we did not yet understand.

While searching for scientists who explicitly rejected the concept of vestigiality, I found surprisingly few modern thinkers advocating this perspective, despite a wealth of such voices in earlier centuries.

As Imam Ali (ʿa) reminds us, “Your remedy is within you, but you do not sense it. Your sickness is from you, but you do not perceive it. You presume you are a small entity, but within you is enfolded the entire Universe.” Our task is not to declare parts redundant, but to learn to read with patience the alphabet of our own existence.

Sabahat Fida is an educator based in Kashmir with Masters in the field of Zoology and Philosophy. She writes at the crossroads of science, religion, metaphysics, spirituality and philosophy seeking common grounds that foster human flourishing .

Related

Gender, Silent Rage, and Autoimmune Diseases