Why AI Art Makes the Internet — And Art — Less Authentic

“…the question arises as to whether this is ‘creativity’ or the mere appearance of creativity masking unethical technical and artistic practices.”

The “death of artistry” is a story we’ve heard many times over: replace “video” and “radio” in the common aphorism and you get “AI killed the artist star.” But there’s more to this current iteration of the anxiety around art than the ones that preceded it. It has to do with the fact that it’s not the medium that’s changed here – it’s the process itself. AI software enables art to be created in seconds, replacing the labor and skill that takes years to acquire.

But with AI art, there’s a more fundamental problem – one that begs the question of the purpose of art itself.

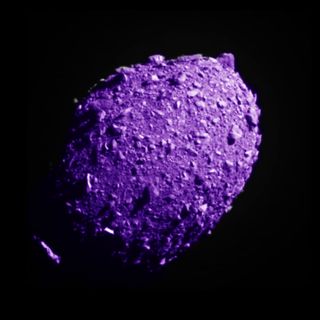

Sure, AI art does capture a sense of wonderment and awe, tugging at curiosities that lay dormant in us and evoking mysteries of a cosmic order we’re simply too small to understand. For a taste, take this series of AI portraits imagining what public figures who died prematurely would look like today, in their old age. Or take ‘Théâtre D’opéra Spatial’ – a piece that won the first prize at the Colorado State Fair. It depicts a group of people staring into a bright void, stylized like a Renaissance painting. All it took to create it was a few text prompts fed to Midjourney, an AI software. A Twitter user pointed out its similarities in style to that of French orientalism in art, which invokes foreignness. “It uses detail to dazzle us without meaning… in the orientalist style, they would frequently mix and combine many different styles of levant and egyptian architecture and culture without regards for what it meant or where it came from, just like how AI art will recombine meaning without its context” the user noted.

Some others are optimistic that the emergence of the artform – if it can be called that – can herald another revolution in art itself.

“When photography showed up, impressionism emerged. What will emerge now, when every imaginable color and shape combination can be made in just a few seconds by an algorithm?” asked one Reddit user.

But with softwares being written in the global north and datasets containing its corresponding bias, there’s a bigger question to be asked about whose gaze is represented in AI art, and what that says about the form itself.

AI art has started conversations on who an artist is, and what we consider art too. But beyond that is a more urgent question of the costs of AI software generating art. What happens when a machine takes seconds to create something – that too based on an immeasurable trove of existing art made by humans? Here is where the ethics get murky, and the cultural conversation around AI art quickly gets philosophical.

The thing about AI art is that it’s easy to make. And there’s a murky definition of who its “artists” are – given that while the authorial intention comes from a human being, the actual art comes from a machine. And that, too, a machine that collects information from a trove of pre-existing datasets – themselves seeped with bias. Previous research has shown that AI reinforces racist, sexist stereotypes because it doesn’t identify biases in the datasets its fed.

“It doesn’t look like they’ve done any curation of the datasets being used… And then they ask the user to take care to not promote harmful stereotypes – effectively washing their hands of any responsibility over this,” observes Divyansha Sehgal, a researcher at the Center for Internet and Society. “All tech is political and all design choices have values embedded inside them,” she adds.

Plus, anyone can use open-source AI art software to make (mostly) anything – whatever they can’t, they can usually bypass. If earlier, people may not have gone through the bother of creating inappropriate or hateful art with their own hands, they can now do so by simply typing in a few prompts into software – and all it takes is a couple seconds. This, coupled with the fact that it can be leveraged for profit for the few people that control the software, is by definition, the antithesis of art as a public good. “Technology is increasingly deployed to make gig jobs and to make billionaires richer, and so much of it doesn’t seem to benefit the public good enough… AI art is part of that. To developers and technically minded people, it’s this cool thing, but to illustrators it’s very upsetting because it feels like you’ve eliminated the need to hire the illustrator,” said cartoonist Matt Borrs, in response to The Atlantic using an AI-generated image in a newsletter rather than hiring and paying for a human illustrator.

Take the recent development that allows users to edit real human faces using DALL-E 2, an AI art platform stylized after famed surreal artist Salvador Dali. Filters and photo-editing tech have already posed questions about the authenticity of art: AI may not only supercharge this debate but infinitely expand the scope for harm.

Related on The Swaddle:

The World Is Turning to AI Weapons to Reduce War Casualties. What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

The other problem with AI art is that it’s relatively easy to produce. It’s why artists are concerned about being the first frontier for robots replacing their jobs – a prospect that should concern us all. “I’m worried about the flattening of expectations of the audience and the marketplace. Just because AI art is available so cheaply, it might flood the market by cranking out “content” that our social media algorithms love so much,” Sehgal adds.

Moreover, by borrowing from images and ideas that already exist, AI art may responding to original prompts but it isn’t necessarily being creative about it. In the process, it could be infringing upon existing copyrighted work – and, more importantly, it disguises something more sinister – copyright infringement, mass production, replication, and ultimately, content creation – as creativity.

“…the question arises as to whether this is ‘creativity’ or the mere appearance of creativity masking unethical technical and artistic practices,” Deepa Singh, an Artificial Intelligence Ethics researcher at the Department of Philosophy, University of Delhi, tells The Swaddle.

While some have argued that AI art is more accessible and addresses the gatekeeping inherent to the world of art, Singh and other artists themselves refute that claim. “The very idea behind AI art generation is not accessibility of art per se, but making machines do art and seeing where they go from there,” she says. The problem with this is the underlying logic of AI as a tool itself, that makes the approach flawed: “the value system of AI is the value system of Silicon Valley, which in turn is also the value system of (mostly) white, male tech entrepreneurs, venture capitalists turned tech evangelists and techno-utopians.”

The ease of generating art – coupled with the copyright and existing dataset issues – lead to a circular situation, in which an AI artist himself is now struggling to claim his own art. One of the internet’s most popular artists, Greg Rutkowski, is now reportedly more searched than Picasso in software prompts. But now, with his own style having pervaded cyberspace while crowding out his own, original work, Rutkowsi hardly has any claim over his own style. “It’s been just a month. What about in a year? I probably won’t be able to find my work out there because [the internet] will be flooded with AI art,” he told MIT Technology Review.

Related on The Swaddle:

An AI Rapper Perpetuated Racist Stereotypes, Showing How Tech Commodifies Culture

Content-generation does not an artform make. For a better analogy of what we’re losing in AI art, turn to AI scripts – themselves an internet joke. Feed a few prompts to a text-box, and an AI software can write a novel, script, story, essay, or term paper in seconds. Are they any good, and do they make sense? Arguably not; they’re just trying different permutations of what already exists. “Artificial art lacks its own intrinsic psychic meaning to the agent. AI agents are not creating art; rather, they are replicating art,” writes S. Will Chambers, in a newsletter.

When something is so easily reproduced, repurposed, and regurgitated, it loses something of its essence. At least, that’s what culture theorist Walter Benjamin argued – nearly a century before AI art even came to exist. He was talking about the easy reproducibility of art in the industrial age – where mechanical reproduction denies art of its “aura”. This is AI art – a compulsive, infinite loop of images all lacking aura for how they’re different iterations of the same few things. Arguably, nothing new, challenging, or subversive is possible when the means of creating art are controlled by big tech.

And given how artists themselves borrow from tradition, experiment with format, and play with ideas, does a machine doing so make things any worse? Arguably, yes. It takes away from the process of creation – adding to a culture of infinite content, ubiquity, and speed that have come to define consumer culture. We may no longer have to wait to see what happens to art when taken to the extreme of consumerism – we’re probably already here.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Why Researchers Working on AI Argue It Could Cause ‘Global Disaster’